Morganton, North Carolina – about an hour east of Asheville and an hour and 20 minutes northwest of Charlotte – is one of those small towns (population approximately 17,500) where textile mills and furniture factories came … and went.

Back in 1992 global automotive supplier Continental came to Morganton … and stayed.

And expanded.

And is now instrumental in the production of what is known by the company as its “Future Brake System,” FBS 2, a semi-dry automotive brake system that deploys a second-generation brake-by-wire system (MK C2) with electromechanical brakes on the rear axle (these brakes are “dry” – as in they don’t use brake fluid) and conventional hydraulic brakes (“wet”) on the front.

Last fall Continental (or Conti as it is colloquially known) received an order valued at about 1.5 billion euros (approximately the same in U.S. dollars at the time due to the exchange rate) for the FBS 2 system that will go into series production with a North American OEM and be introduced in 2025.

The Morganton plant – a 210,000-square-foot facility where some 500 people work – has long produced the MK C1 brake system. And now it is going on to the MK C2, which is a sophisticated system Conti developed with BMW that combines the master cylinder, brake booster, and control systems into a single 4.3-liter system. What’s more, it is based on Conti’s Multilogic Architecture and provides features including 100%-efficient regenerative braking. Yes, the FBS 2 approach is about facilitating the stopping of electrified vehicles that can include levels of autonomy. It has over-the-air (OTA) update capability.

The MK C2 system is a sophisticated piece of automotive mechatronics. People often describe something as “state of the art.” Arguably this is.

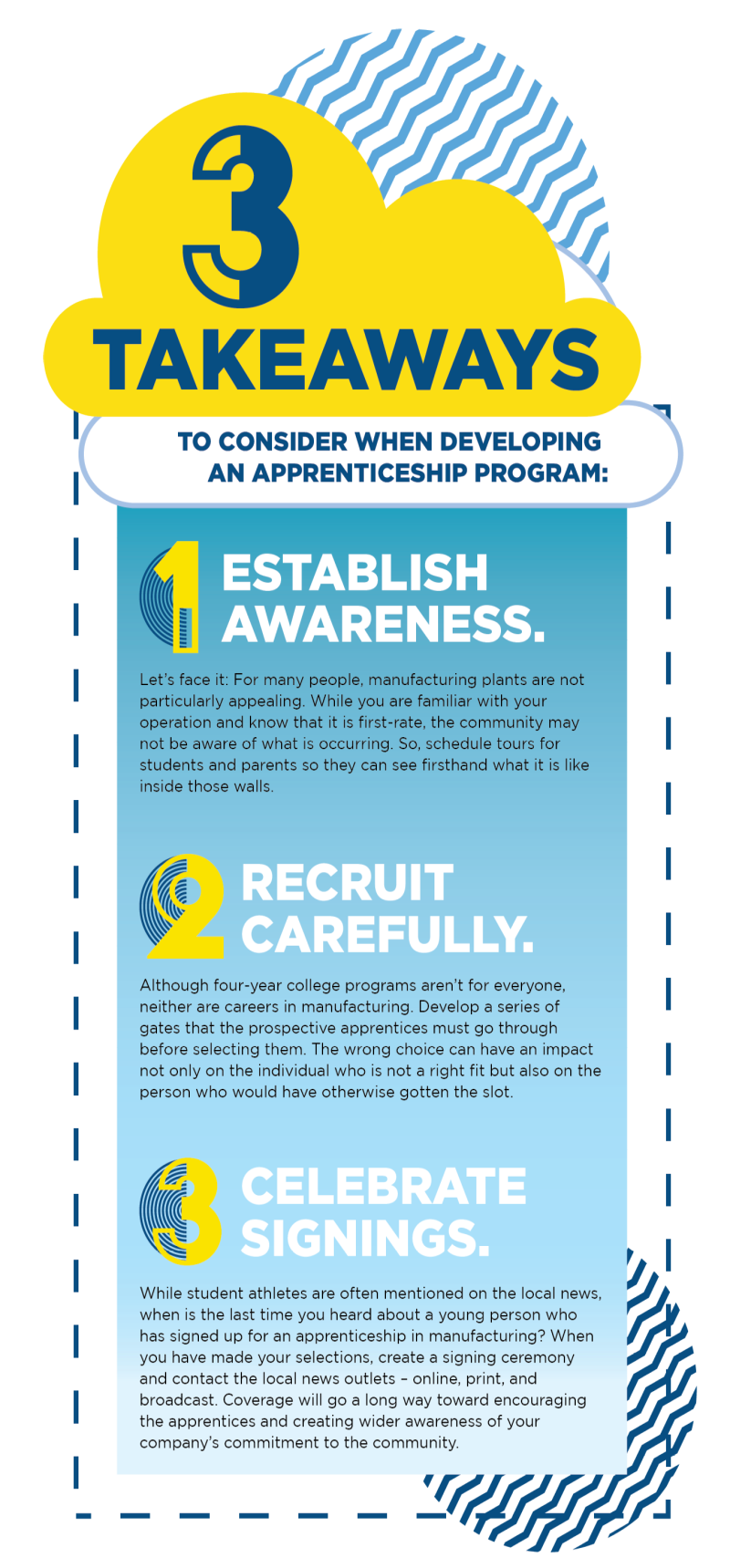

Eric Childers, manager, manufacturing engineering, at the Morganton plant, says that some of the local people thought that brake pads or brake rotors were being produced at the factory, not state-of-the-art (yes, I said it) braking systems.

The Program

Childers, who has been with Continental since 1992, helped establish an apprenticeship program at Morganton in 2014. Brad Silver, who has been at the factory for 23 years and is also in manufacturing engineering, works with Childers on organizing and recruiting for the program.

Childers says that the program is focused on, not surprisingly, mechatronics: mechanical, electrical, hydraulic, pneumatic, robotics, automation, programming. The goal is to develop people who are multicraft-capable, multiskilled. The factory is chock full of robots and lasers, material handling, and servocontrols. The environment is clean and bright. It is a far cry from the local garage cluttered with fugitive unmounted tires and shop rags whose red is long forgotten.

As is the case with apprenticeship programs throughout the United States, Childers and Silver worked with the state of North Carolina to establish the program (initially, the North Carolina Department of Commerce managed the state’s apprenticeship program; now it is handled by the North Carolina Community College System: www.apprenticeshipnc.com), which combines both on-the-job training and classes that lead to a two-year degree in applied science with a specialization in areas like mechatronics or industrial systems technology. In the case at Conti, there are 5,200 hours of on-the-job training. Silver says that most of the students carry 16 credit hours per semester, so when they are not in class, they are accumulating 24 hours in the plant.

And the thing that is initially quite surprising to the people in the program – and their parents – is that there is a paycheck for 40 hours.

Getting There

Silver says that each year in February, he and Childers visit local high schools to talk to students and teachers. He acknowledges something that plenty of people don’t want to admit: a four-year degree isn’t right for everyone. There are some people who are good with their hands and like working that way.

In March they bring in students for tours of the Morganton facility. And, importantly, they ask teachers to take the tour as well.

Those who express an interest participate in a weeklong orientation program in April. Then Childers and Silver look through the documentation they’ve accumulated through these preliminaries to determine who will be asked to participate in a six-week internship program that occurs in June and July.

Based on that, they decide who will be asked to join the apprenticeship program at Continental. While a lot of that may sound familiar – after all, there are plenty of companies of varying types that have apprenticeship programs at their organizations – there is something that makes what is happening at Continental Morganton somewhat different.

A Difference

Duke. The University of North Carolina. NC State. Wake Forest. One of the things that the state of North Carolina is renowned for is college basketball, and to say that being recruited out of high school to play college ball is a big deal is to understate the case.

Say you’re a junior or senior at Draughn High, East Burke, or one of the other high schools in Burke County, North Carolina. Say you’re pretty good at basketball or another sport. Maybe not great, but good. And you see on social media young women and men who seem just like you being lauded for declaring for a college.

You’re going to feel envious.

Childers says that when they make the final decision on the next class of apprentices, it isn’t simply a matter of sending an email or making a phone call. Silver points out that when a student athlete achieves something, the local papers acknowledge it.

So Childers, Silver, and the people with whom they work internally and externally hold a signing ceremony. They make sure that those who have achieved the opportunity get public acknowledgment for it. The people who are accepted into the program are likely to see their names in The McDowell News or the Morganton News Herald.

Not only is this good for the young people who have been accepted, but it is good for the younger people in the area who may hear about the Continental program through the signings. Silver says that there is an emphasis at the plant to get young people – ninth graders, for example – to tour the facility. And Childers notes that they even hear from parents who want to know about the availability of openings in the program.

It isn’t enough for an organization to think what it is doing is special – the people must make sure that others see that it really is special.

What young person wouldn’t want to stand on stage and get their picture taken for their decision to pursue a career in manufacturing?

Nowadays

Since Childers and Silver have been at this for more than a decade, the question arises: How is it different today than when they began?

One of the differences is a result of letting people see the inside of the facility to understand that this isn’t a dark, dank, and dirty factory from days gone by. Actually seeing robots and rows of touch-screen controls and the like can make a big difference.

And then there are programs like “How It’s Made” that show that manufacturing is interesting and not repetitious or dull as was once the case, such as in high-volume industries like automotive. Childers says there is an array of YouTube videos showing how operations are performed that are readily accessible.

What’s more, today’s young people are essentially digital natives; a 16-year-old was born the same year as the iPhone.

The Downside That Isn’t

Some people are reticent to make the investment in an apprenticeship program – and it is an investment of time, commitment, resources, and more – because they think that at the end of the program, when the journeyman certification is granted, the newly minted employee will leave.

And while most of the people who have been through the Continental Morganton program stay, Silver says that if someone decides to leave, they congratulate that person.

That is worth repeating: They congratulate the person who has decided to move on.

Part of this goes to the commitment that the company has to the community: The program isn’t just about achieving a highly skilled workforce to make advanced technology braking systems but rather about advancing the entire area and the people who live there.

Part of this is knowing that those who leave will always remember where they came from and how they were treated.

Some who have moved on have recommended to people at other companies that they might want to work at Continental Morganton, and the organization has gained some good employees as a result.

Coda

You talk with Childers and Silver for just a few minutes, and their belief becomes evident that what they are doing, what Continental is empowering them to do, has benefits that can make a huge difference to individuals, their families, and their community.

The pride is palpable.

If you have any questions about this information, please contact Gary at vasilash@gmail.com.