According to the Economic Policy Institute, the U.S. trade deficit with China alone cost 3.7 million American jobs between 2001 and 2018. The United States has gone from being the world’s manufacturing powerhouse, responsible for the lion’s share of global industrial production just after WWII, to being unable to produce critical Personal Protection Equipment (PPE) for the COVID-19 crisis in a timely manner.

In the mid to late 1940s, we produced half of the world’s manufacturing output, much higher than the 28% that the world’s factory, China, produces today. Currently, at least half of what we consume is imported, with major supply chain gaps, such as PPE and rare earth minerals. As a result, U.S. manufacturing output growth has been slowing for the last 20 years.

Even the slow U.S. growth in the last decades (Exhibit 1) is probably overstated due to how the government values the increasing efficiency of electronic devices and the implied value-added increases due to offshoring. If manufacturing output was measured in tons or units of products, manufacturing has almost certainly declined. For example, steel production is down by more than 30% from the 1970s.

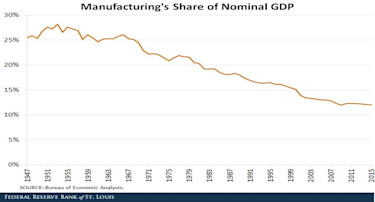

Manufacturing’s share of GDP collapsed from about 27% around 1955 to about 12% today (Exhibit 2).

Exhibit 2

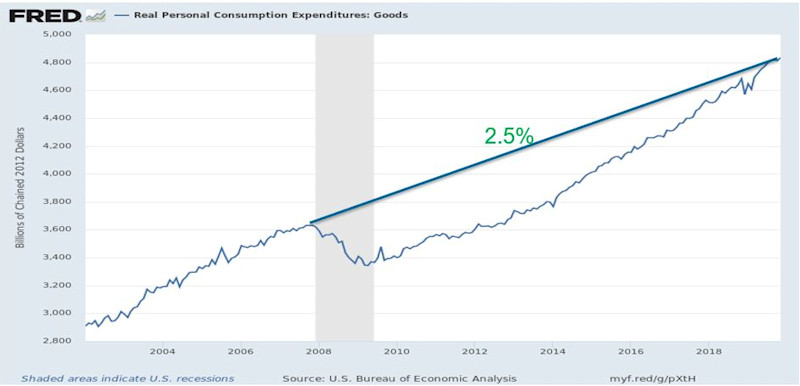

Differing perspectives might propose that a shrinking manufacturing share is due to our post-industrial society and that we mainly consume services rather than goods. However, this concept is dispelled in Exhibit 3, which illustrates that United States goods consumption has grown at least as fast as the GDP (Exhibit 3).

Exhibit 3

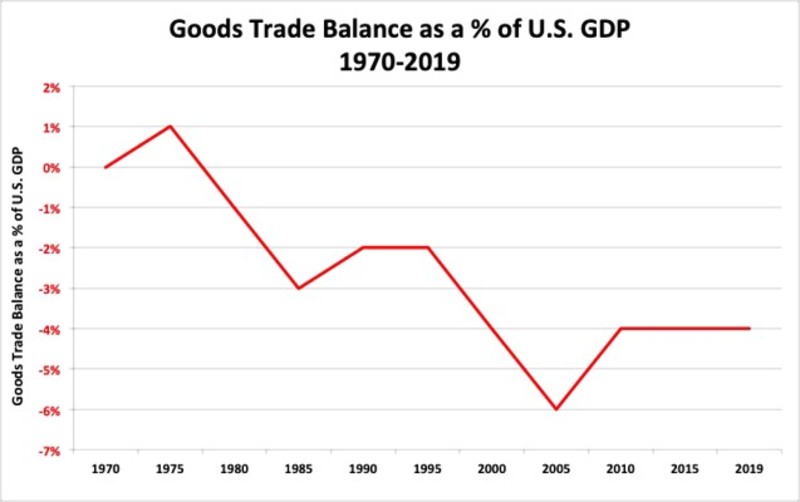

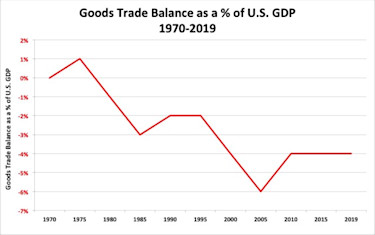

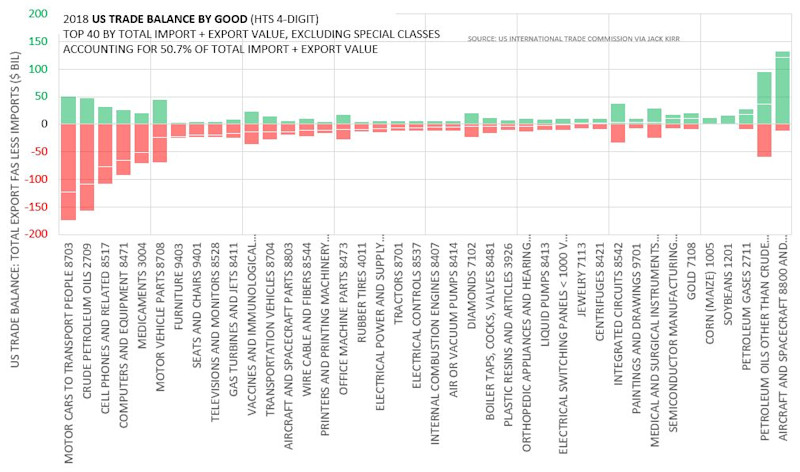

The United States no longer makes the majority of what we consume, and the lack of self-sufficiency triggered the need to rebuild our supply chains. The magnitude of the situation can be seen in Exhibit 4.

Exhibit 4

The United States had a major trade surplus during and after WWII. The surplus declined to zero by 1979 as Europe rebounded. Since then the United States had increasing trade deficits while Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Mexico grew as suppliers to the U.S. market. The deficits increased further after China joined the WTO and now average about $800 billion per year.

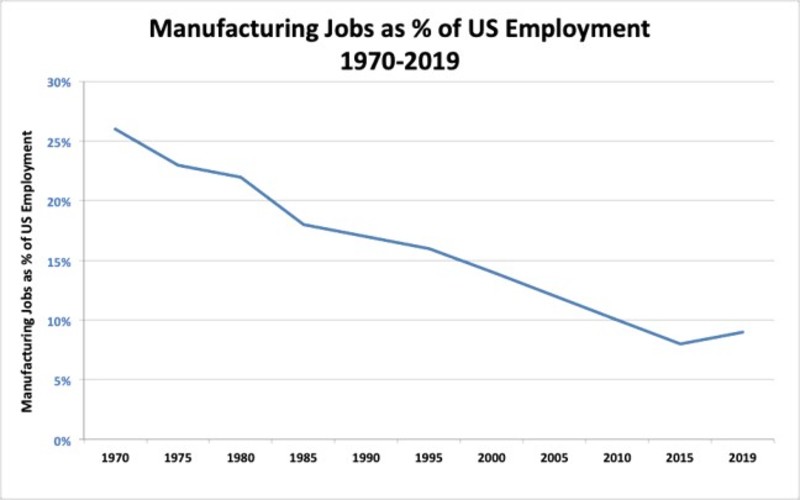

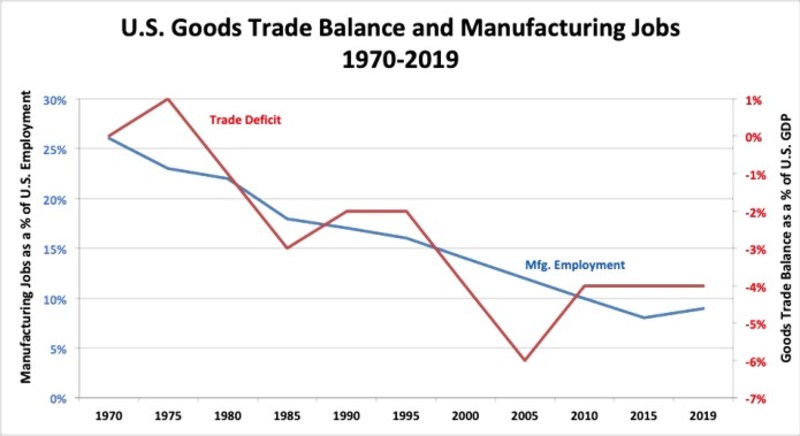

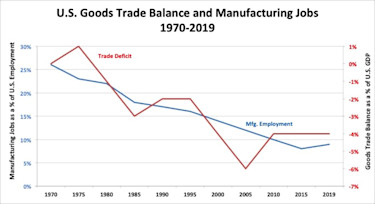

Primarily because of the increasing trade deficit, U.S. manufacturing employment as a percent of total U.S. employment declined dramatically from about 26% in 1970 to about 9% today (Exhibit 5).

Exhibit 5

The loss of about six million jobs is primarily due to the trade deficit and offshoring. A relatively small percentage is due to increases in productivity, which has only grown about 0.4% per year from 2007 to 2019. The strong correlation of trade deficit and declining manufacturing employment is clear in Exhibit 6.

Exhibit 6

The trade deficit is not uniform across all product categories. The United States is relatively strong in a few legacy high-tech, heavy industry categories, such as airplanes, defense, construction equipment, and jet engines (Exhibit 7). Otherwise, our profile is akin to a developing country with strong surpluses of commodities at the right of the chart and trade deficits in high-tech goods, such as computers and smart phones, on the left. The green bars are exports, the red are imports. Units are $ billions.

Exhibit 7

Our large trade deficit, a measure of offshoring or lack of self-sufficiency, is primarily due to the United States not being price competitive on a broad range of products. Key conclusions from a recent survey by Plante Moran and the Reshoring Initiative show that about 70% of offshoring decisions are price driven, and the average offshore price is about 60% to 80% of the equivalent U.S. price, depending on country and product. The survey does show that about 30% of the imports have prices within 30% of the U.S. price and thus might be feasible for reshoring.

Over the last few decades, the nation has lost millions of good-paying manufacturing jobs to reduce costs by way of offshoring. The U.S. trade deficit with China alone cost 3.2 million jobs between 2001 and 2013. Job losses occurred in every state, primarily in manufacturing. Offshored jobs diminished American employment opportunities, depressed wages, and had a dramatic negative effect on the domestic economy. Offshoring has also negatively impacted the world environment through higher carbon emissions and other pollution from some developing countries and from long distance transport.

Companies made the decision to offshore to take advantage of low wages, less regulation, and increased price competitiveness, often ignoring many hidden costs. They concentrated on short-term gains for shareholders, instead of investing in capital equipment, innovation, and workforce training. U.S. society began to promote “college for all” putting less emphasis and investment in skills-based training, credentialing, and apprenticeships. Consumers encouraged offshoring by demanding the cheapest goods. The government allowed the U.S. dollar to appreciate 300% vs. our trading partners in the last 40 years.

ReEvaluate and ReEngage Although there are continuing concerns regarding China’s industrial policies, the United States has limited control over China’s initiatives. However, we have unlimited control over our competitiveness initiatives and our ability to achieve our ambitions. Let’s collaborate to support American competitiveness and rebuild a U.S. manufacturing powerhouse.

THIS ARTICLE WAS ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED ON IMTS BY HARRY MOSER ON AUGUST 17, 2020.