The Rise of Urban Air Mobility

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 will have profound consequences on many parts of the U.S. landscape and economy as only something with a spend of some $437 billion can. For those in the manufacturing space, the IRA has a very large carrot: Companies can get $35 per kilowatt-hour of battery cells produced, $10 per kilowatt-hour for battery modules built, and a 10% tax credit on costs used to produce materials.

And there’s the National Electric Vehicle Infrastructure (NEVI) program: $5 billion for the construction of a national EV charging network, including requirements for charger assembly in the United States as well as the fabrication of the steel or aluminum enclosures, and will, in 2024, require 55% of components to be sourced domestically.

But in March 2023, the “National Aeronautics Science & Technology Priorities” report came out of the executive office with important implications. One way of looking at this is that the Wright Brothers put the United States in pole position at the start of the aviation industry, and the U.S. government wants to keep it there. From the report:

“The aeronautics enterprise is an integral part of the U.S. economy, annually generating 4.9 percent of U.S. gross domestic product—$1.9 trillion in total economic activity in 2019—and more than 10 million jobs. The aeronautics sector is also a major exporter, the second largest manufacturing export sector in the United States, generating $148 billion in exports in 2019. … Continued investment in state-of-the-art aeronautics research and development (R&D) is critical to ensure the continued vitality of this important sector.”

On the one hand, it is about national defense. And on the other, the commercial space, which, according to the priorities, “accommodates approximately 2.3 million passengers and 66,000 tons of cargo on 25,000 flights daily.” And: “These numbers are projected to increase.”

Among the technologies that the government plans to prioritize in this space, “with the potential to transform aviation … creating new industries and jobs,” are advanced air mobility (AAM) vehicles, including electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft.

And if there is something that is going to transform air travel in a way that is analogous to how electric vehicles are going to change the way people go about their daily drives, it is eVTOLs – and they’re going to be making the change sooner, not later.

Economic Approach

Commercial companies are developing eVTOLs and advancing technologies while taking economic factors into account. They are working on craft that can attain FAA certification to transport people. They are also working to assure money will be made on building and operating these aircraft.

In Archer Aviation’s 2022 fourth-quarter earnings call this past March, Archer’s chief financial officer, Mark Mesler, explained that the Archer model has two approaches. One is Archer Direct, which will sell the Midnight eVTOL directly to customers; and the other is Archer Air, which will provide a service with its equipment. He anticipates a 50-50 revenue ratio.

Mesler said that an eVTOL flight between Manhattan and Newark Liberty International Airport, which takes approximately 10 minutes, could be priced at $6 per passenger mile – similar pricing to a terrestrial rides haring vehicle – and assuming that its four seats are occupied on each trip and there are 25 trips per day, 365 days per year, that would be revenue of $3.2 million per year.

This is not simply a theoretical calculation. On Nov. 10, 2022, Archer and United Airlines announced they plan to operate flights between the Downtown Manhattan Heliport and Newark International. Then, on March 23, 2023, the two announced a route between downtown Chicago and O’Hare Airport. Both routes are expected to be operational in 2025.

Not a Few, but Many

United is committed to eVTOLs: in August 2022, it made a $10 million pre-delivery payment to Archer for 100 aircraft.

“Wait a minute,” you think. “100 aircraft? How long is it going to take for that delivery?”

Potentially quite a bit less time than you might think.

That’s because there is another company that is working with Archer: Stellantis. This global automotive OEM is collaborating with Archer on a factory being developed in Covington, Georgia. This 350,000-square-foot plant, expected to open in 2024, will have a capacity of 650 aircraft a year. There are already plans on paper to build out the plant for a 2,300 unit capacity.

Not only is Stellantis providing Archer with high-production expertise, but it is also providing up to $150 million in equity capital.

Thomas Paul Muniz, Archer’s chief operating officer, said that they’re looking at achieving high volumes by leveraging automation and using “processes that are more similar to what you see in automotive.”

The Toyota Production System, Too

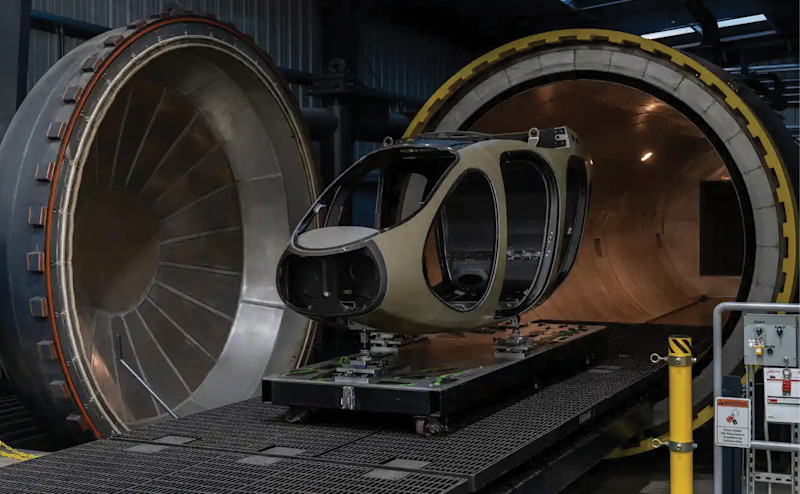

Archer isn’t the only eVTOL company in this space with a somewhat analogous approach to developing an entirely new passenger aircraft. In late April 2023 Joby Aviation announced signing a long-term agreement with Toyota Motor Corp. for powertrain and actuation components. What’s more, Toyota has been working with Joby on the design of the pilot production line for the aircraft, as well as participating in various projects.

Keiji Yamamoto, president of Connected Co., Toyota Motor Corp., said, “Our mutual goal is mass production of eVTOL and helping Joby apply the best practices of the Toyota Production System in meeting high quality, reliability, safety, and strict cost standards.”

JoeBen Bevirt, founder and CEO of Joby, said of Toyota, which also happens to be the largest external shareholder in the company with an investment of approximately $400 million, “Their expertise has helped put us on track to deliver, at scale, an aircraft that we believe is truly best-in-class.”

Another company participated with Joby in the development of the eVTOL. According to a company spokesperson, “The airframe is a carbon fiber composite we have developed in-house, in collaboration with Toray.” Toray Industries is one of the leading composites suppliers on the planet.

While Joby is currently operating its pilot production facility in Marina, California, the company will soon announce the location of its major production operation.

Delta and the Air Force

It is also worth noting that Joby also has a relationship with a major air carrier: Delta Air Lines has made an upfront equity investment of $60 million in Joby, with the potential of investing up to $200 million. And there is an operational relationship between them, with the aircraft providing services to Delta’s airline customers, initially in New York and Los Angeles.

And although this has concentrated on the commercial aspects of the two companies, going back to the “National Aeronautics Science & Technology Priorities,” Joby also has a $131 million contract with the U.S. Air Force (e.g., it will be delivering two of its five-seat eVTOLs to Edwards Air Force Base early in 2024).

Things like flying cars are still fanciful. The creation of eVTOLs is the real thing.

EVs on Rails

When Chevrolet launched the Volt in 2019, it didn’t want the vehicle to be referred to as a “hybrid.” After all, Toyota pretty much owned that word with the Prius in the same way that Kleenex owned the term for the paper facial tissue.

The Volt has an electric motor and an internal combustion engine. But that engine functions mainly as a generator, charging the battery that powers the motor that turns the wheels. It is a series hybrid. The Prius is a parallel hybrid.

So instead of calling the Volt a “hybrid,” the folks at Chevy insisted that it be called an “extended-range electric vehicle.”

While that may have seemed somewhat innovative at the time, if not revolutionary, do you know what else is an “extended-range electric vehicle”?

Locomotives.

And these hybrids have been commercially available since 1925 (as switchers in railyards). Through the 1930s, a leading manufacturer of diesel-electric locomotives was Electro Motive – which was owned by General Motors (it sold the business in 2005).

Efficiency for the Distance

Today the architecture of a locomotive has a diesel engine (with roughly 4,500 hp) that powers an alternator; its electrical output goes to the traction motors that power the wheels and pull the freight. According to the most recent figures from the U.S. Bureau of Transportation Statistics, there are 23,544 freight locomotives (i.e., not passenger trains) on the nearly 140,000 miles of freight rails in the United States.

The Association of American Railroads calculates that a train will move a ton of freight some 480 miles on a single gallon of fuel, making a freight train three to four times more fuel efficient on average than a truck. The organization points out that while railroads handle about 40% of the long-distance freight volume in the United States, they are responsible for 1.9% of transport-related greenhouse gas emissions.

As efficient as these giant hybrid vehicles are, there is still that fuel: diesel. The combustion of diesel fuel results in particulate matter, nitrogen oxides, carbon monoxides, and other pollutants.

So railroad companies and locomotive manufacturers are looking at alternatives in order to reduce their carbon footprints.

The Wabtech Portfolio Approach

One company with a strong position in this space is Pittsburgh-based Wabtec Corp., a leading manufacturer of locomotives. It has been in the train business for more than 150 years. It originally began in 1869 as Westinghouse Air Brake Co. and since then has grown both organically and through acquisition. The latter included the 2019 merger with GE Transportation, which had been around since 1907 and produced its first locomotive in 1912. Interestingly, those early Electro-Motive diesel-electric locomotives used GE motors. Today, Wabtec has a global installed base of locomotives of about 23,000 units.

Wabtec is taking a portfolio approach to reducing emissions in the locomotives it produces, such as using liquified natural gas and performing research on various biofuels.

Importantly, Wabtec has developed FLXdrive, a fully battery-electric locomotive.

No diesel. Just electricity.

In a three-month pilot – revenue service, so this wasn’t an engineering trial – conducted with BNSF Railway in San Joaquin Valley, California, they found the locomotive, which has 2.4 megawatt hours of lithium-ion battery storage, saved what would have been more than 6,200 gallons of diesel fuel and prevented 69 tons of carbon dioxide emissions from being produced during the 13,320-plus miles of freight hauling.

This performance was an industry first.

Presently FLXdrive locomotives are in production at the company’s complex in Erie, Pennsylvania. One will be delivered this year to Australian mining company Roy Hill. It has an energy capacity of more than twice that of the pilot locomotive: 7 MWh. Roy Hill will be using it in an iron ore hauling operation – trains that are on the order of 1.6 miles long.

(If you want to know how small the world is, consider this: The batteries that Wabtec is using are Ultium batteries – developed by General Motors.)

If you’ve ever seen the front of a freight train (given the lengths, you’re more likely to see the railcars) you might have noticed that there is generally more than one locomotive. (This grouping of locomotives is known as a “consist,” with the emphasis on the first syllable.) The Roy Hill consist that the FLXdrive will be used with has four diesel locomotives. Although FLXdrive will replace just one of them, Roy Hill estimates a double-digit reduction in fuel costs and emissions.

Optimization

Philip Moslener, Wabtec’s vice president, advanced technology, says one of the important elements to operating the consist efficiently is the use of what is, in effect, a railroad-scale version of an automotive smart cruise control system. The Trip Optimizer system takes into account the makeup of the train, terrain, and other parameters and then operates the engines in an optimal manner.

An important element of achieving operational efficiency for the FLXdrive is – again, something you might be familiar with if you have an electrified vehicle in your driveway – is regenerative braking, taking the kinetic energy of the brakes and using it to charge the batteries (otherwise, it would mainly be lost to heat).

There is another undertaking, Moslener explains, with great potential: using hydrogen to power locomotives.

Last November Wabtec, Argonne National Laboratory, and Oak Ridge National Laboratory announced cooperative research and development agreements (CRADAs) to develop the hardware and software control strategies that could be used to use hydrogen in existing engines. Moslener says locomotives can be in service for up to 50 years and that the modification “would help decarbonize more quickly without having to get rid of equipment.”

And Soon H2

Then there is the second hydrogen track Wabtec is taking: fully powering a locomotive using Hydrotec hydrogen fuel cell systems – which happen to have been developed by GM and are being produced at Fuel Cell Systems Manufacturing in Brownstown, Michigan, a joint venture between GM and Honda.

In this case it would be a replacement of the diesel engine with the fuel-cell modules.

Moslener points out much of this depends on the availability of economical green hydrogen (i.e., hydrogen produced by using renewable electricity for the electrolysis of water). He says that the U.S. Department of Energy’s Hydrogen Shot program could go a long way to accomplishing this cost competitiveness. The goal of this program is “111”: $1 per kilogram of green hydrogen in one decade.

Here’s something to consider: The Industrial Revolution was largely powered by the development of the steam engine. One of the uses of the steam engine that literally transformed transportation was the locomotive.

BrightDrop: Bringing EV Delivery Vehicles to a Neighborhood Near You

One of the abiding consequences of the pandemic is that people discovered that they could buy essentially everything from the comfort of their own home or office. For parcel deliveries – USPS, UPS, FedEx, Amazon, etc. – seven days a week became the rule, not the exception.

According to the Pitney Bowes Parcel Shipping Index, in 2022, U.S. companies and consumers shipped, received, and returned 21.2 billion parcels. That’s 58 million a day, some 674 parcels per second.

And Pitney Bowes sees growth: a 5% CAGR between 2023 and 2028, reaching 28 billion parcels in 2028.

So there is room for more delivery vehicles that can efficiently, economically, and environmentally do the work.

A New Brand

General Motors, while known more for its passenger vehicles than its commercial products, has plenty of truck-building experience: The GMC brand was known as General Motors Truck Company when it was established in 1911.

In January 2021, with growing demand for commercial trucks, especially electric versions – and associated software and services – GM announced the establishment of BrightDrop, described by Mary Barra, GM chairman and CEO, as “a new one-stop-shop solution for commercial customers to move goods in a better, more sustainable way.”

GM cited analysis from the World Economic Forum that was released in January 2020 (before any lockdowns) that showed that among last-mile deliveries, same-day delivery was growing 36% per year and instant delivery by 17%.

So, the idea of electric delivery vehicles – vans as well as carts – made tremendous sense to GM. Rather than simply thinking, “Yes, this looks like a good opportunity, so let’s pursue it,” people at the corporation worked with FedEx, so the day BrightDrop was announced, Richard Smith, FedEx Express’ regional president of the Americas and executive vice president of global support, was able to say, “Our need for reliable, sustainable transportation has never been more important. BrightDrop is a perfect example of the innovations we are adopting to transform our company as time-definite express transportation continues to grow.”

FedEx was the first customer for the electric delivery vans.

The Demand

The first five of what was then an order for 500 vans were delivered to FedEx by Dec. 21, 2021. (By June 2022 there were 145 more delivered.) And there have been plenty more multiple-vehicle orders from companies, including Walmart, DHL, and Merchants Fleet. There are now over 25,000 ordered on the books.

To accommodate the demand, GM invested some $800 million to retool its CAMI production facility in Ingersoll, Ontario, Canada, which had been producing Chevrolet Equinoxes prior to the BrightDrop vans.

The Development

BrightDrop’s Matt Armstrong says the development of the Zevo 600 (the first of the delivery vans, with the smaller Zevo 400 launching in 2024) was predicated on people from the GM Global Innovation organization and design staff being essentially embedded with drivers from companies, including FedEx, to see what their days were like. GM didn’t want to make just another step van but something that was a marked improvement. The electric technology contributes greatly.

For example, typically, delivery drivers get in and out of their vehicles over 100 times a day. The Ultium battery platform is placed low so the step-in height is lowered, making it easier on drivers’ knees. They designed the seat not only for comfort, but to facilitate ingress and egress. The typical lever to set the parking brake is replaced by a push-button. Cargo lights in the storage area (over 600 cubic feet and a payload capacity of about 2,200 pounds) are turned on and off by motion sensors.

The Parts Bin

Notably, the BrightDrop vans are the fastest-built vehicles – from concept to market – in GM’s history. Twenty months.

Part of that, Armstrong explains, is predicated on the Zevo engineers being able to take advantage of the learnings from another large electric vehicle that was being developed at the time, the GMC Hummer EV.

What’s more, while there is sometimes criticism leveled at companies like GM for using the “parts bin” in developing vehicles (i.e., using the same components in a Chevy as in a Cadillac, for example), Armstrong notes that the GM parts bin provided BrightDrop with an advantage because the parts bin contributes things from the steering wheel to push-buttons to the Zevo 600, thereby keeping down costs.

The Outlook

While the uptake of electric vehicles by consumers in the United States remains to be determined, Armstrong says they see a huge opportunity going forward with electric delivery vans for several reasons.

For one thing, fleet operators are looking at total lifecycle costs, and BrightDrop calculates that in terms of maintenance and fuel costs, the Zevo 600 can save over $10,000 per year compared to a comparable diesel-powered vehicle.

For another, companies like FedEx have publicly committed to transforming their pickup and delivery fleets to all-electric vehicles (in FedEx’s case, it intends to do so by 2040).

So, we go back to the start of this: In mid-April, after the U.S. Treasury announced its guidance regarding the critical mineral and battery component requirements as related to the Inflation Reduction Act, GM announced: “Fleet customers including for BrightDrop and the Chevrolet Silverado EV will benefit from the $7,500 commercial incentive.”

The transportation transformation has a lot to do with what the U.S. government is doing.

To read the rest of the Transportation Issue of MT Magazine, click here.