On Sunday, Sept. 7, 2014, in Chicago, something started before the opening of IMTS – The International Manufacturing Technology Show in the Emerging Technology Center (ETC) that has reverberated through our industry ever since.

It was the day before IMTS 2014 officially started. Forklifts zoomed around the floor. Carpet was still being laid. Workers hurried to get exhibits in place.

It was also media day, when journalists from around the world got to walk the floor – albeit a floor that was still taking shape – and, if they took AMT up on its invitation, they had the opportunity to see something that had never happened before – not just at IMTS but at any trade show or event, anywhere:

A car was being printed in the AMT ETC at McCormick Place.

The official poster for the Strati, the world's first 3D printed car, which was created at IMTS 2014. (Image courtesy of Ricky Neff)

Bonnie Gurney, AMT vice president, strategic content and partnerships now; AMT director of communications then: “We were absolutely confident, or maybe 95%, it was going to happen.”

Jay Rogers, CEO of Haddy Inc. now; co-founder and CEO of Local Motors then: “It was like a moon shot. And until you land on the moon, you haven’t done it.”

Rick Neff, CEO of Rick Neff LLC now; manager of market development for Cincinnati Inc. then: “That Sunday morning, when we started the machine, no one could look you in the eye and say that it would work.”

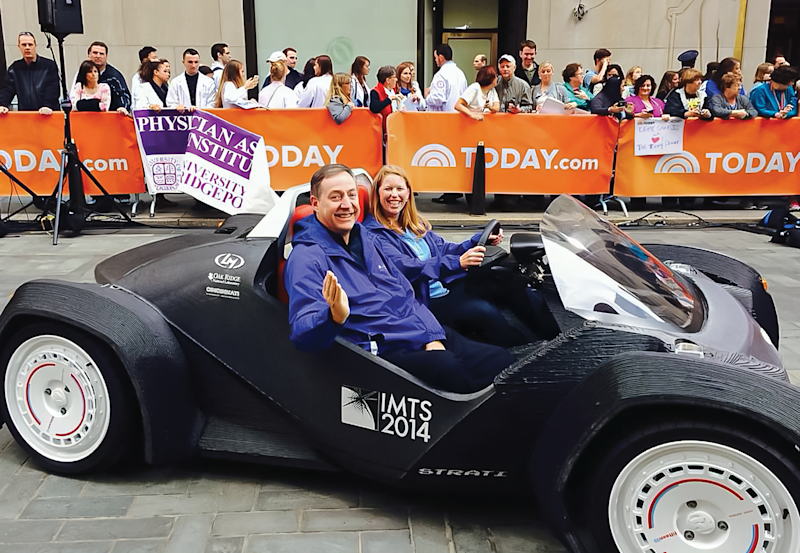

But when all was said and done, the team accomplished what had previously been unthinkable: They built the first 3D printed car in the world, the Strati.

The Strati was a remarkable success, even going on to appear on the “Today Show.” It has since helped drive the entire additive industry to where it is today.

Not Bits and Pieces. The Whole Thing.

In 2005, Rogers visited Craig Bramscher, who had started Brammo, a vehicle manufacturing company in Ashland, Oregon. That’s when Rogers began to understand that a car could be 3D printed. Rogers says Bramscher showed him the printing of a vehicle-like structure with a urethane paste that came out looking like a marshmallow. It set for about an hour, then a spinning blade was used to cut away material so that it looked like a car.

Rogers says he began querying an array of composite companies about whether they had a material that could be extruded, quickly set, and then machined.

In 2007, after a couple years without gaining any traction, he pretty much gave up and put the thought on hold.

That same year, Rogers founded Local Motors, a company that took a revolutionary approach to the design (leveraging crowdsourcing) and building (at microfactories) of vehicles. And the idea of printing a car stayed with him.

It’s important to note that when Rogers uses the phrase “printing a car,” he means essentially the whole thing, structure and chassis, not individual sections that are subsequently assembled into a vehicle.

Where It Began

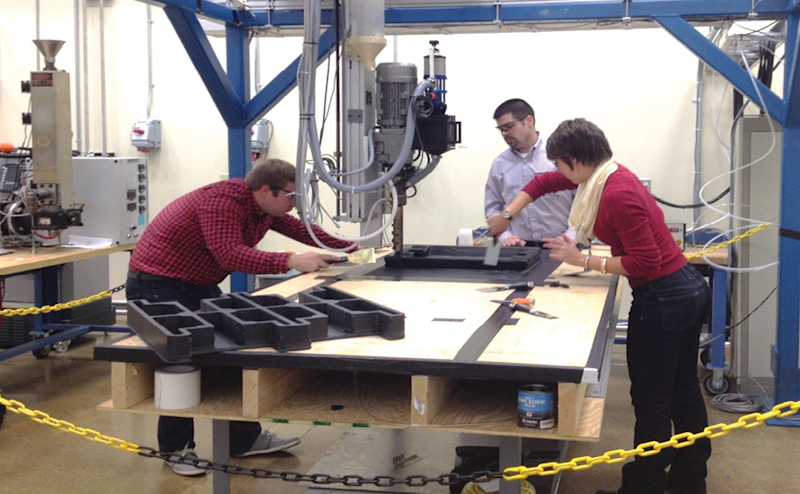

As Lonnie Love, the then-corporate fellow at the Manufacturing Demonstration Facility at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL) and the current national security programs fellow at Sandia National Laboratories, recalls: In 2013, he and his colleagues worked on what was to become known as the Big Area Additive Manufacturing (BAAM) machine, based on work that had been done at Lockheed Martin by Slade Gardner and his colleagues. The intent of the Lockheed Martin machine was to print aerospace tooling.

“They decided not to invest in the technology and asked us if we’d like to take over,” Love says. So, the equipment moved east to Oak Ridge.

Neff, in his role as market development for Cincinnati Inc. (CI), a company involved in sheet metal laser cutting systems and other tech, visited ORNL in 2013 and saw the machine. He talked to Love about commercializing the technology. The two organizations began working on developing the tech.

Love and one of his colleagues visited CI and saw one of the company’s laser cutting gantry systems. Love says they determined that they could replace the laser with an extruder and turn the cutter into an additive machine. (And there were also some other non-trivial things, like developing a heated bed for the machine, developing the control strategy, determining process parameters, increasing the capability of the extrusion system ...)

That CI machine became the unit deployed in Chicago for the Strati. (It also became the basis of a product line that CI had for some years.)

And then there was another important encounter.

“I ran into a guy at a conference in Boston, Rick Neff, who said that I needed to meet Lonnie Love,” Rogers recalls.

Neff could see that what Love and his colleagues were doing at ORNL was aligned with Local Motors’ different approach to vehicle manufacturing.

Love says, “Jay Rogers visited, saw the technology, and asked if I thought we could print a car.”

The key elements were coming into alignment.

The original gantry printer at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. Through a series of meetings, the idea was born to create a gantry-style extruder that would be capable of printing an object the size of a car with carbon fiber-reinforced ABS plastic. (Image courtesy of Rick Neff)

AMT Involvement

At IMTS 2012, the Local Motors booth in the Emerging Technology Center raised eyebrows. It built a car there on the show floor: the Rally Fighter.

While the Rally Fighter wasn’t 3D printed, this was the first time that AMT featured an attraction that was built in real time on the show floor.

As Gurney remembers: “This generated a new energy for the show ... People came back each day to see the progress of the project. What's new, what’s different, what were the challenges, etc. And in the 2014 trade show world, IMTS was leading the way in experiential exhibits. It was a real car that was assembled live at IMTS.”

After his visit to ORNL, Rogers met with AMT staff members– President Doug Woods; then-Vice President of Exhibitions and Communications Peter Eelman (who is now AMT’s chief experience officer); and Gurney – and told them that he wanted to 3D print a car at IMTS 2014.

Gurney says that they were all-in on the idea. It would help them with their mission of “educating people and showing them the awesomeness of manufacturing.” To be sure, the visitors at IMTS are well-versed in what manufacturing is all about, but in 2014, the idea of additive manufacturing was, for many of them, pretty much just that: an idea – if it was thought of at all for their shop floors.

Rogers wasn’t pitching just building a car at IMTS – he was committed to a car that would drive out of the Emerging Technology Center. “There were a lot of people along the way who said to just have it roll. I said, ‘Are you kidding?’ We said we would print this thing and drive it off the show floor.”

They got the green light from AMT.

Achieving the Design

Local Motors went to its community and launched the 3D Printed Car Design Challenge. It ran for six weeks. During that time, there were more than 200 entries from designers in more than 30 countries.

The winner was Michele Anoé of Italy. He designed what he called “Strati,” or “layers” in Italian.

Rogers notes two things about Anoé’s design:

By naming it Strati, it helped provide focus as to how it would be built: layers.

The winning design is reflective of the international nature of IMTS. “Michele said that only in America could you get an Italian to come to design a 3D printed car.”

And one thing that Neff points out about the Strati design: “It doesn’t have any doors.” Doors are hard to print. (Doors are also hard to stamp, weld, and accurately fit on vehicles, even today.)

The design was selected in June 2014, three months before the show.

Achieving the Process

The Strati weighs some 1,400 pounds.

To put that into context regarding the monumental task the team was taking on, Love says that in 2014, a large, commercially available printer had a deposition rate of about five cubic inches per hour and a built volume of less than 20 cubic feet.

“It would have taken over a year to print the Strati using conventional 3D printing,” Love points out. “However, even going at 10 pounds per hour – about 250 cubic inches per hour– wasn’t fast enough. Our models showed that this was about four times too slow.”

So, they needed to find a means to deposit the material more rapidly.

And as for the material they were using, they sourced an ABS material from chemical manufacturer SABIC* that was reinforced with 20% chopped carbon fiber. Neff says that not only does the carbon fiber contribute strength to the structure, but because of the way the fibers orient as a result of extrusion, “When it cools down, it lowers the coefficient of thermal expansion along the length of the extrusion by about an order of magnitude, so it lowers the stresses in the part and helps keep the part from warping.” What they didn’t want was delamination.

“We discovered a ‘Goldilocks’ effect,” Love says of the process. “For a given flow rate on the extruder, if you went too fast, the part got too hot and wouldn’t hold its shape. If you went too slow, it got too cold and would crack.”

Two of his ORNL colleagues, Vlastimil Kunc and Brett Compton, developed the models that would help get the printing “just right.”

But there was still the question of the deposition rate. Love says they worked with Tim Womer, who at the time was with Xaloy, a developer of screws, barrels, and other components for extruders and injection molding machines. They developed a new screw for the extruder that would increase throughput to 40 pounds per hour.

“We took delivery of the screw at ORNL the week before IMTS,” Love says.

They put it on the ORNL machine on the Thursday of that week and verified its performance. On Friday, they flew the screw to Chicago.

“Saturday, ORNL had a team install the screw and calibrate the system, then started printing Sunday morning at 7 a.m.,” Love says.

In Addition to Additive

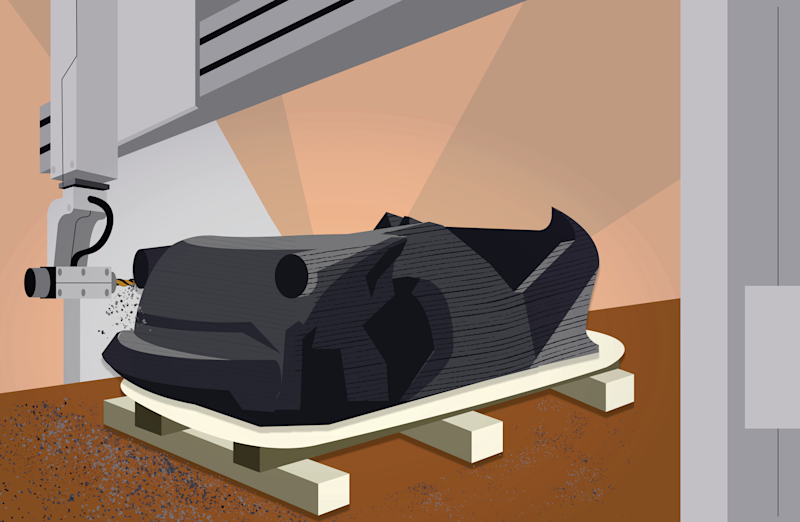

While the Strati structure was printed, some areas still required machining, such as assembly points for the electric drivetrain. Neff notes that the machining was tricky because the structure was still hot when it was being milled and was consequently shrinking as it cooled, so they had to chase the tolerances – literally.

The machining was done on a machine from Thermwood Corp., a company that sold mainly into the wood and plastics industries at the time. (Thermwood would go on to add the Large Scale Additive Manufacturing (LSAM) line of equipment to its offerings.)

A Cautionary Tale

Remember the 20% carbon fiber loading of the material?

“We needed at least 20% to give us the stiffness needed to constrain the residual stress and prevent distortion,” Love says. But, he recalls, about an hour into the build, two ORNL colleagues came to him and said the car “was curling up on us.”

They determined that the problem was that someone had changed the loading from 20% to 15% carbon fiber-reinforced ABS because they could get it for free. Apparently, the engineer who made the decision thought that a 5% difference wouldn’t be that much, but as Love points out, “In reality, that’s 25% less reinforcement.”

They continued to deposit the material. “We decided to forge ahead, believing that if we could get far enough along in the print, the structure would increase in stiffness and stop distorting.”

It did. But it made machining the structure more difficult.

Being economical doesn’t necessarily result in savings.

The machine ran around the clock.

In the early hours of Tuesday, Sept. 9, 2014, the 3D printing was complete.

Making It Move — and Then Not

Not everything in the Strati was 3D printed, including things like the seats, steering wheel, instrumentation, tires, and windshield.

And not the propulsion system.

Rogers says that he and his colleagues looked around the global auto industry to find an electric propulsion system that could be used for the Strati.

They concluded that the Renault Twizy, which is categorized in Europe as a “quadracycle” rather than “automobile,” had a 13-kW motor and 6.1-kWh lithium-ion battery pack that would fit the requirements.

So they set about to get a Twizy that they would deconstruct to get the necessary components.

Renault, of course, is based in France.

However, as Rogers and his colleagues soon discovered, European vehicle manufacturers build for the European market to meet European standards set by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe – and build for the U.S. market to meet the standards set by the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards.

That meant they couldn’t go to Paris, buy a Twizy, and ship it back to Local Motors in Phoenix, Arizona.

They thought about going to Europe to buy the propulsion system.

They couldn’t do that, either.

Eventually they were able to work with U.S. government regulators to buy two Twizys (Rogers said they didn’t want to be in a situation where something didn’t work on one of them without a backup).

But it came with a hitch:

Once they had used the Twizy system for the Strati, they had to destroy it as well as the two vehicles – and prove it to the government.

Which explains why Rick Neff currently has the original Strati, minus its means of propulsion, on jack stands in his parents’ garage. It can roll but not drive.

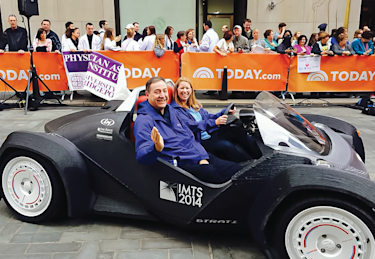

But at IMTS 2014, it was powered, and Rogers and Woods took it out for its initial spin.

The two men drove the Strati on a red carpet out of the ETC and down the Grand Concourse of McCormick Place toward the East Building. From there, they entered McCormick Place Square, where the police and media greeted them with much fanfare.

“It was an exhilarating experience,” says Woods. “The team had dedicated tremendous effort to come up with new solutions for the project, and its execution shows the inspiration and innovative spirit of IMTS. It’s what we strive to bring to every show.”

For the second run, Gurney got in.

“It was an unbelievable feeling,” she remembers fondly. “But what kept going on through my mind was: ‘Now what do we do– how do we top this?’”

People Power

While the creation of the Strati was a technological tour de force, everyone involved stressed one aspect of the project that allowed it to succeed: Teamwork.

As Love recalls, for example: “In 2013, we had a cobbled-together prototype system at ORNL. But working in a team changed the pace we could move.”

And one of the lessons that Neff says that the Strati project taught him beyond any doubt: “The way to accelerate innovation is through collaboration of diverse people – backgrounds, education, job experience.”

But One More Element

Looking back, Lonnie Love says that there was something else needed to create the Strati on the floor of McCormick Place in 2014, to do something that had never been done before with a technology that we now take as a given but which then simply wasn’t ready for prime time:

“It was an amazing team of industry and government working together. But we needed that stress of IMTS. We needed a hard deadline, failure not an option, high profile ... If we fail, we look like idiots – which we probably were, but it was a hell of a lot of fun.”

In the decade since that remarkable IMTS, the AMT Emerging Technology Center has continued pushing the boundaries of manufacturing technology. It has featured such moon shots as a carbon-fiber printed house; an automated cell linking a Hurco CNC, a Universal Robot arm, and a Hexagon CMM using the MTConnect™ standard; technologies underpinning the Giant Magellan telescope; and a space habitat designed as a living and work environment for astronauts and researchers living on the moon and Mars. Still, among such exciting exhibitions and achievements, the Strati stands tall.

At IMTS 2024, to celebrate its 10-year anniversary, Gurney, Love, Neff, and Rogers will reunite on stage. Make sure to visit IMTS.com to register to catch up with the Strati crew and see what future technologies will be unveiled in the ETC this year.

To read the rest of the Additive Issue of MT Magazine, click here.